Introduction

The Nahuas had long preserved their histories. In the early sixteenth century, when the Spaniards appeared upon the scene, they were the guardians of an already centuries- old tradition known as the xiuhpohualli (SHOO-po-wa-lee). The word has tended to be translated as “year count,” faintly redolent of a charming primitivism, but it would perhaps better be rendered as “yearly account.”

… there were pictorial texts, and there were oral performances. The first set of words referred to a custom of painting timelines on long rolls of maguey paper or bark, where the traditional yearly calendar was marked out with well-known glyphs (reed year, flint- knife year, house year, rabbit year, and then again reed year, and so on), and pictographic writing along the line referred to the major events of each period. These writings, like other types of writings (including those organizing religious ceremonies, or tax collection, or landholdings), were called in tlilli in tlapalli.

The painted histories were rich texts in their own right. They were able to convey not only lists of subjects but also actions — in other words, a true narrative. They harbored the beginnings of a systematic phonetic orthography. They boasted complex glyphs that cross-referenced each other and sometimes changed each other’s meanings when placed in certain pairings, in the same way that two different spoken words, like in tlilli in tlapalli, became a third entity when placed together. However, the paintings were never, no matter how complex or beautiful or worthy of attention, the whole story. The audience might crane their necks to see the undulating lines that marked the well-known and sometimes treacherous rivers, or to get a better view of the flaring flames that marked the conquests their grandfathers had made, but even at such visually exciting moments, they were also poised to listen, waiting for the speaker to proceed. The words, the flowing narrations, were the heart of the matter.

He might give a litany of ancestors if he was emphasizing continuity, or break out at a certain point and perform a miniature one-man play to illustrate a past political predicament. Sometimes the dialogue was funny and made the people smirk or even laugh outright. Sometimes it was enraging, and when a historical figure asked a certain question, the audience was ready to shout a response. Soon it was another history teller’s turn to step forward and represent the perspective of a different lineage or clan. People turned expectantly to hear the alternate view.”

— Camilla Townsend, Annals of Native America

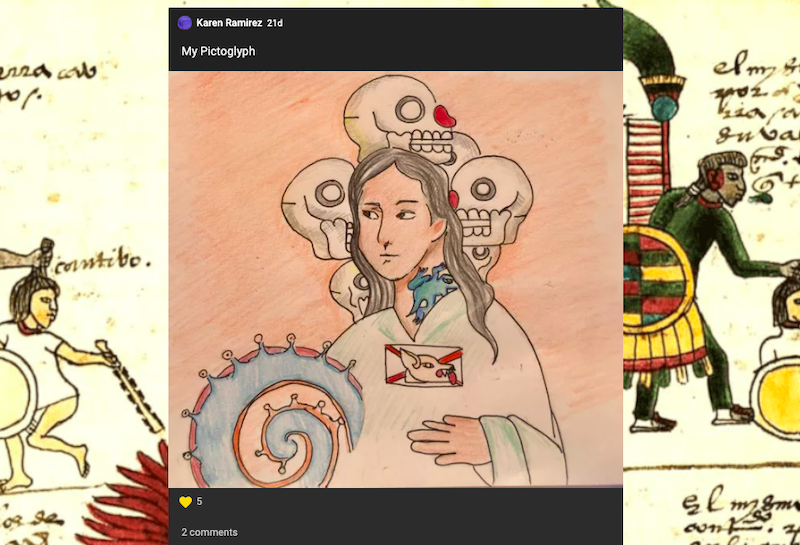

For this activity, students used Nahua pictures and glyphs for inspiration to respond to one of the guiding questions from class.

See their responses here: https://padlet.com/destevao/pictoglyph